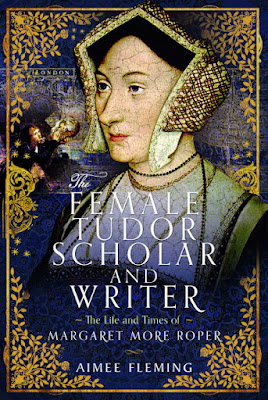

Today I am delighted to hand over the blog to historian and author Aimee Fleming, whose new book, The Female Tudor Scholar and Writer: the Life and Times of Margaret More Roper, was published this week.

*****

What drew me to write about Margaret More Roper? What makes her life a good story and a good subject for a book?

I first came to learn about Margaret More when I was studying at university, almost 20 years ago now! I chose the dissertation topic of ‘Women’s Education in Tudor England’, and this inevitably led me to read about the well-known educated ladies of the time: Elizabeth I, Katherine Parr, Queen Mary I, and then Margaret cropped up. The more I read on the subject, the more Margaret was held up as the example of an educated Tudor woman, and yet there was so little actually about her and her family. All of the sources talked about her father and the wider events of the Tudor court, with just a small mention of Margaret and even less words given to her sisters and wider family.

|

| Sir Thomas More and his descendants - painting by Lockey based on Holbein |

This is not unusual when dealing with Tudor women. Women were often seen as unimportant, or incapable of learning beyond what was expected of them – raising children, running a household, being chaste and respectful to the men in their lives. But, unlike many women of the time, Margaret’s abilities were well known. She had a reputation both in England, at the court of King Henry VIII and even with the King himself, and in Europe and further afield. Referenced as that ‘ornament of Britain’ by Erasmus, a close friend of Thomas More’s, and held up as an example to anyone, any woman. An inscription, recently found in a Qur’an held in the Bodleian Library, reads:

‘…whom in special Margaret Roper was alone the most noble any that ever lived in this world,for beauty for science for virtue for excellence…’

She comes up again and again in the records, mentioned in letters to and from her father when he was on his travels or on court business, or she appears in portraits of the whole More family, showing her front and centre of the group and dominating her side of the picture. She was involved in some of the most high-profile events of King Henry VIII’s reign, and wrote (alongside her father), letters that have gone on to colour the way we imagine life to have been during the turbulent 1530s.

She was daring, taking on the authorities on more than one occasion. She put herself in danger of following her father to the Tower for rescuing her father’s head from ‘being devoured by the fishes’ and keeping it and other possessions, despite them being dangerous for her to hold onto.

|

| Lucy Madox Brown painting of Margaret rescuing her father's head |

Publishing her translation of Erasmus’s studies of the Lord’s Prayers into English was risky as it had never been done before, especially by a woman. In doing so she paved the way for generations of women who followed, including her own daughter, to write and put their words out using printing presses and the English language.

And yet, a huge number of people have never heard of her.

Most will have heard of Thomas More, and while they may not know the ins-and-outs of his life, they at least know that he was important. In recent times depictions of Sir Thomas have shown a daughter there with him. They may even have mentioned her name. In A Man For All Seasons she is presented to the King as an obstinate and determined young woman, but not necessarily shown in the best light. This may be most people’s introduction to Margaret, but I do not necessarily think it’s a fair first impression. Pictures of Thomas, mostly produced in the last hundred or so years, often show Margaret interacting with her father – hugging him as he enters the tower, visiting him while there. They show her loyalty and devotion to her father, but have her very much in a supporting role and overshadowed by him. This doesn’t accurately show Margaret’s abilities, her courage in the face of adversity, and her determination to carry on her father’s work.

This is why Margaret made such a good subject for a book. Her story has been overshadowed by the men in her life – her father by his actions and writings, or her husband for his biography of Sir Thomas More which came to be so crucial as a source for all historians that have come since. But just a little digging reveals just how influential Margaret was and what impact she had, and still has, on our knowledge of the period. She was a scholar in her own right, and commanded respect even from King Henry VIII himself. There is evidence that she and her father worked together on several of his written works, and her determination to save so much of her father’s writings and correspondence means that without Margaret, our knowledge of the period would be significantly less detailed.

As soon as I started to learn more about her, Margaret’s life became a passion for me. She was formidable, a real trailblazer and deserves to be brought out of her father’s shadow. Writing the book was a challenge as what we know of Margaret is scattered and must be pieced together, but I hope that I have done her justice and shown that she deserves to be remembered and acknowledged.

*****

Author Bio:

Aimee Fleming is a historian and author from North Yorkshire. She is happily married, with three growing boys and a whole host of pets. She studied history at the University of Wales, Bangor and then later completed a masters at the University of York as a mature student. She has a passion for history, particularly the Tudors and all things Early Modern.